How do we come to agree?

The big news over here at Lux this week was that Grace Isford joined us as our newest investor, based in New York City. She’s going to be investing at the intersection of web3/crypto, data infrastructure and AI/ML, an area where there is an incredible amount of deep tech being built such as the future of information theory and distributed consensus. Welcome Grace!

It’s on the latter subject of consensus that I want to explore more today, since it’s perhaps the single most important challenge facing democratic life today. Consensus, or the ability of different people to agree to the same set of facts and conclusions, is the key property of any functioning social system. When it works, decisions are rapidly made, morale is high, direction is clear and social organizations can be quite resilient and effective. A lack of consensus leads to stasis and sclerosis, of trying to “build” consensus rather than doing the actual work of execution.

In science, consensus is the acceptance of experimental results into the canon of a particular field. Peter Galison, the renowned historian of science at Harvard, built his career on a book titled “How Experiments End.” A scientist conducts an experiment and gets a result, perhaps a result that upends some accepted facts within a discipline. What happens next? A single experiment with a novel result could just be a fluke, a statistical oddity or perhaps a misconfigured instrument. So the scientist does another experiment, maybe with the exact same procedures or perhaps with a different approach that would make the result more resilient to criticism.

Such work begins the recursion at the heart of science: more evidence is collected, more scientists get involved. But when do we know that the experiment has been validated? And conversely, when should we throw out previously accepted results that now appear to be overturned? Galison gives a tremendously erudite depiction of this subject (one best left to reading the actual book), but the stupidly simple answer is: it really depends, and it’s complicated. Underlying that complexity though is the process of science itself, which handles divergent views in a specific way in order to synthesize a consensus.

We see this dynamic in VC partner meetings. There are procedures, guidelines and benchmarks to make a decision, systems that are designed to help a group of diverse and divergent investors come to consensus around an opportunity. Yet, every investment is unique, each in a different market with a different product sitting at a different stage. There’s an equivalent “How Investment Decisions End” — every time, the consensus function needs to be adapted to meet the needs of each company that presents and ensure the most accurate and highest conviction decisions. Divergence of opinion is a hallmark of any great investment firm.

Yet, some of the strongest mechanisms here don’t have any divergence at all. Distributed consensus is one of the most powerful developments that blockchain technology offers, and it’s part of the reason why web3 proponents can at times feel almost religious in their fervency. The ability of otherwise unrelated computers to come to an agreement around “state” (i.e. the data on the blockchain) without referencing the same, shared dataset is an incredibly powerful tool — the exact tool, in fact, that scaffolded the very civilization we are a part of.

Yet, even as computers build better and more robust consensus mechanisms, not just to compute token ownership but also to validate external information through oracles and other approaches, human society itself is tapering its abilities to generate consensus.

Take a look at Russian aggression against Ukraine the past few weeks. This week, markets gyrated as the media disseminated news that Russia was pulling back troops from the Ukrainian border on Tuesday, with the S&P 500 up on Tuesday and reaching a weekly high on Wednesday. Then U.S. intelligence agencies announced that Russia had in fact buttressed its forces on Ukraine’s border all along, sending shares tumbling about 4% over Thursday and Friday’s trading sessions.

Getting an accurate assessment on Russian troop levels is not an easy problem, but it’s also not something that only a handful of intelligence agencies can do. Planet Labs (a Lux family company), Capella Space, and other commercial satellite imagery providers have the means to capture and track Russia’s movements for the general public. Are there troop carriers moving? Where are they moving to? What’s their capacity?

All of us can verify more of that information than ever before. Take one example of a bridge analyzed by Nikkei Asia:

A military pontoon bridge appears over the Pripyat River, less than 6 km from Ukraine’s northern border with Belarus, in commercial satellite imagery taken Tuesday by U.S.-based Maxar Technologies. In images from U.S.-based satellite operator Planet Labs, the structure is absent on Monday but present Tuesday.

While disinformation and misinformation are both key elements of Russia’s strategy in this phase of the contest, it’s not as if consensus is impossible. There is now enough density of satellite sensing, on-the-ground video sources, and open-source intelligence that anyone can now develop an independent view on the conflict. There may well be a range of views given the available evidence, but there is more than enough data to make finding an “end” to the analysis possible.

What happens though when the information has been analyzed, the results are in, and yet consensus remains elusive? This has been the crisis of American politics. On a wide range of issues, debates are everlasting and ultimately fruitless, leading to irreconcilable differences as I highlighted a few weeks ago on "Securities” in “American Civil War 2.0.”

Why can we find scientific consensus, investment consensus, token consensus on the blockchain and even mostly consensus around Russian troop movements, but not around areas like health or immigration or infrastructure or climate change?

It’s simple: most of the consensus has already been established in the fields among the former. Scientists share a common set of principles, experimental approaches, and procedures to drive toward consensus. Venture funds like Lux, even if they are heterogeneous in making decisions, share a common perspective on what makes a distinguished investment and the kinds of evidence that should exist to identify them. Blockchain protocols rigorously apply consensus algorithms to their database, and analysts of Ukraine have constraints and norms that push them to at least some form of consensus.

Society, meanwhile, doesn’t have all those layers of consensus to build upon for new decisions. There’s no algorithmic blockchain ensuring that the basic facts of reality are cross-validated, or the scientific method to ensure that evidence is considered with appropriate context. Consensus is recursive, and without better consensus functions around values and tradeoffs, it’s impossible for a nation to make decisions.

America and much of the West escaped that lack of deep consensus simply through abundance. Multiple values and tradeoffs could be supported by building institutions that allowed them all to coexist. Venture funds can’t make every investment and scientists can’t accept every contradictory result, but wealthy nations can support a wide range of consensuses, each underwritten in parallel.

Despite the optimism that emanates from the business self-help bookshelf, building a singular consensus across a nation is monstrously hard work. Yet, if we are to lift above malaise and build a new future, we do actually have to agree on what that new future should look like and what paths are available for us to get there. Without more of that critical work, we might have a new book to write: “How society ends.”

Conjunction Junction, what’s your function?

Talking about consensus and dissensus, the theme of Lux’s quarterly LP letter for this past quarter was “the power of ‘and’.” The core message is that we are moving from a period of conjunction to one of disjunction — the crowded wisdom of everyone investing in the same basket of high-growth SaaS stocks is being supplanted by a varied strategy as investors in the public markets and even among venture firms scramble to find their own alpha in this much more complicated, post-Covid world.

Josh Wolfe posted excerpts of the LP quarterly letter to Twitter on Thursday — if you didn’t catch some of the highlights, definitely check them out.

The power of And: AI + fusion

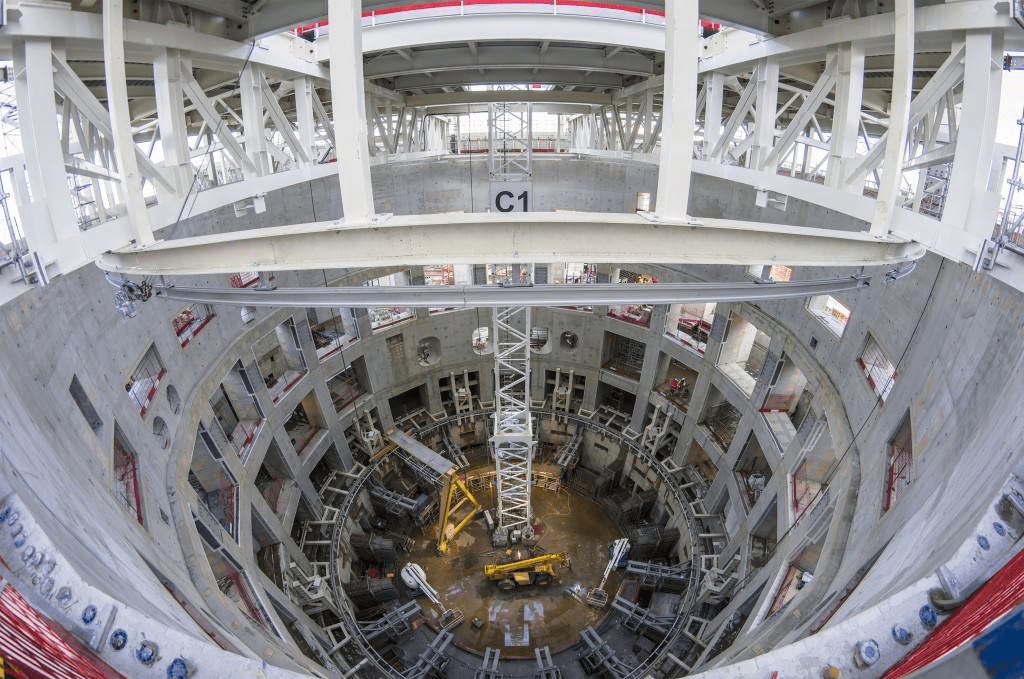

The ITER tokamak device. Image Credits: Oak Ridge National Laboratory / Flickr / Creative Commons

Last week in "Securities,” I wrote about positive developments in nuclear energy in “Fission today, fusion tomorrow.” Nuclear fission got a boost from France, which announced it would build a series of new reactors over the next decade. Meanwhile, scientists in the United Kingdom sustained a record-breaking fusion reaction for about five seconds — proving that the design of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) in southern France is workable (of course, we'll know for sure when ITER launches, since that is how experiments end).

There was further bold news on the fusion front this week. DeepMind, which is owned by Alphabet, published a paper in Nature on Tuesday that demonstrated how deep reinforcement learning could be used to control the superheated plasma in a tokamak device — the exact type of doughnut-shaped magnetic containment vessel that is at the center of the ITER.

The plasma in a fusion reactor is too hot to be contained by any form of traditional material. So instead, a tokamak uses magnetic power to contain plasma within a very strict bound of a vacuum at the center of a doughnut-shaped metal shell. The magnets have to be carefully and continuously calibrated to contain the plasma though, which is unstable and can breach the vacuum at any time if not precisely contained.

DeepMind showed that its AI model could adjust the voltage of those magnets thousands of times per second in order to optimally contain the plasma. That should improve the viability for sustained fusion power — bringing the world one small inch closer to abundant energy and an entirely new energy security paradigm.

Lux Recommends

- Shaq Vayda recommended this Wall Street Journal piece by Christopher Mims looking at the future of physical stocking technology and its effect on supply chains.

- Shaq also recommended this new paper in Science, where scientists successfully used a technique known as ex vivo lung perfusion to convert a lung from blood type A to blood type O. By removing the blood antigens, the transformed lungs could be used by any recipient, expanding eligibility for organs, particularly patients with type O blood who have the least access.

- Adam Goulburn recommends this documentary video by DeepMind that covers the company’s development of AlphaFold, which used deep reinforcement learning to solve the challenge of predicting how proteins will fold based on their underlying amino acids.

- Sam Arbesman recommends this essay by Michael Nielsen and Kanjun Qiu that explores outliers in the scientific literature and how best to build a scientific funding system to encourage these great papers.

- Every few years, there is a great critical teardown of TED Talks and their progeny. Oscar Schwartz joins this tradition with an essay in The Drift, dichotomizing the facile and gauzy optimism of the talks with the tough and deep innovation that the world actually needs.

That’s it, folks. Have questions, comments, or ideas? This newsletter is sent from my email, so you can just click reply.